The Daoist/Taoist philosophers were known for their unforced approach to life, serving as a welcome relief to stultifying Confucian perfectionism. And the Daoist Master, Zhuangzi, more than perhaps any other Chinese philosopher, came to exemplify the anti-rational creative mindset so coveted by the Chinese literati of various ages.

“Making a point to show that a point is not a point

is not as good as making a nonpoint to show

that a point is not a point.”

– Zhuangzi

Zhuangzi (庄子, Zhuāngzǐ) followed in the footsteps of Laozi (老子, Lǎozǐ, aka Lao-Tsu, Lao-Tzu) though it’s likely this iconoclast would have resisted classification of this sort. His body of writing, at times, drew upon imaginary characters engaging in intriguing dialogues in order to highlight relativist dilemmas and lightly mock conventional philosophers such as Kongzi (孔子, Kǒngzǐ, aka Confucius), Mengzi (孟子, Mèngzǐ, aka Mencius) and Mozi (墨子, Mòzǐ).

In a testimony to his legacy, the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy states that elements of Zhuangzi’s naturalism, along with themes found in the text attributed to Laozi, helped shape Chan Buddhism (Japanese Zen) — a distinctively Chinese, naturalist blend of Daoism and Buddhism with its emphasis on focused engagement in our everyday ways of life.

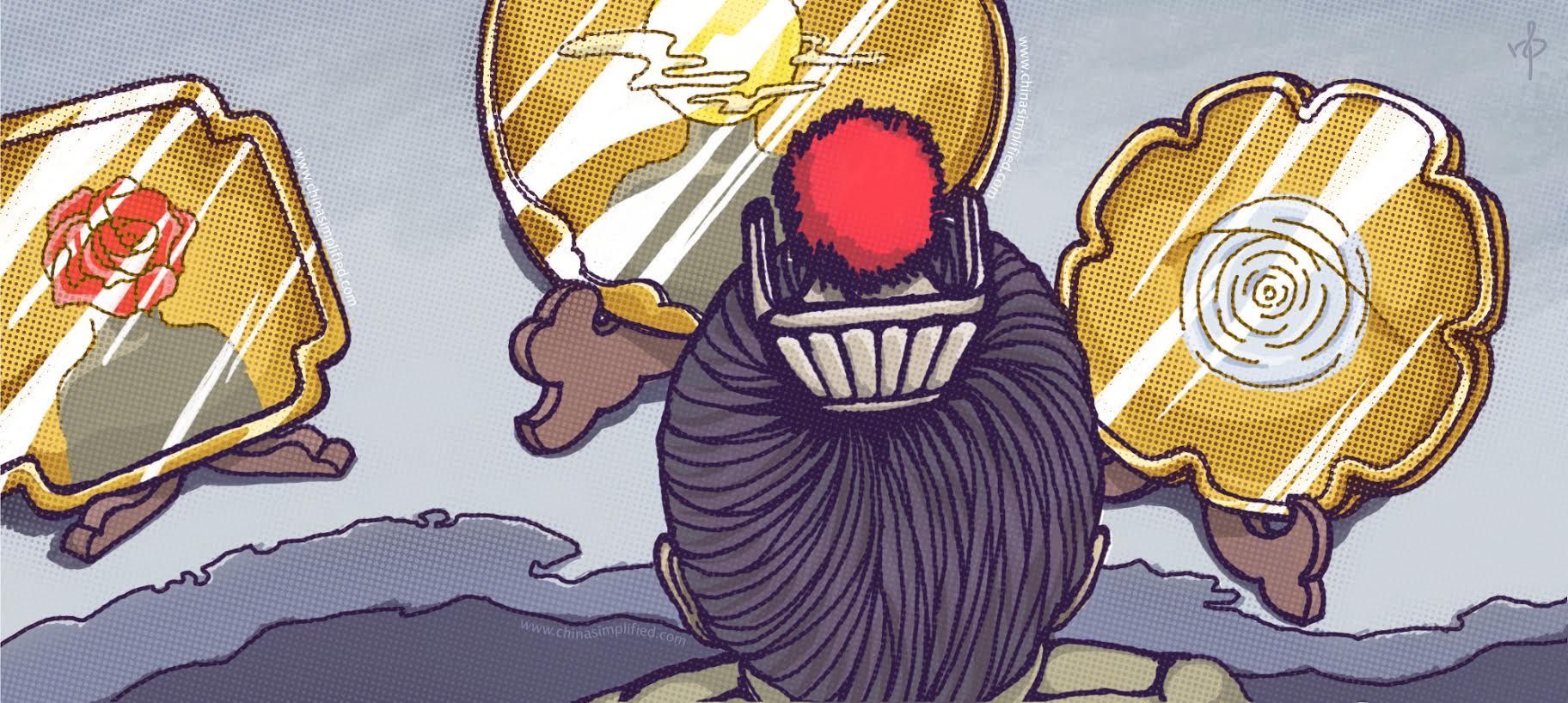

Determining Right and Wrong

Here’s one of our favorite Zhuangzi passages, sourced from Readings in Classical Chinese Philosophy by Bryan Van Norden and Philip J Ivanhoe, to demonstrate Zhuangzi’s view on the futility of fixed definitions such as “this” and “that” or “right” and “wrong” in an ephemeral world:

即使我与若辩矣,若胜我,我不若胜,若果是也,我果非也邪?我胜若,若不吾胜,我果是也,而果非也邪?其或是也,其或非也邪?其俱是也,其俱非也邪?我与若不能相知也。则人固受其黮闇,吾谁使正之?使同乎若者正之?既与若同矣,恶能正之!使同乎我者正之?既同乎我矣,恶能正之!使异乎我与若者正之?既异乎我与若矣,恶能正之!使同乎我与若者正之?既同乎我与若矣,恶能正之!然则我与若与人俱不能相知也,而待彼也邪?

Once you and I have started arguing, if you win and I lose, then are you really right and am I really wrong? If I win and you lose, then am I really right and are you really wrong? Is one of us right and the other one wrong? Or are both of us right and both of us wrong?

If you and I can’t understand one another, then other people will certainly be even more in the dark. Whom shall we get to set us right? Shall we get someone who agrees with you to set us right? But if they already agree with you how can they set us right? Shall we get someone who agrees with me to set us right? But if they already agree with me, how can they set us right? Shall we get someone who disagrees with both of us to set us right? But if they already disagree with both of us, how can they set us right? Shall we get someone who agrees with both of us to set us right? But if they already agree with both of us, how can they set us right?

If you and I and they all can’t understand each other, should we wait for someone else?

Said another way, the process of glorifying right and wrong causes us to lose touch with the Way.

The Way has never been bounded; words have never been constant. All the meanings we assign to words are equally relative to perspective.

This Daoist profound acceptance of life as it comes is echoed by the Indian author and teacher Jiddu Krishnamurti who once explained his secret to life as: “I don’t mind what happens.”

It only seems “right” to let Zhuangzi have the last word:

“How do I know that loving life is not a mistake?

How do I know that hating death is not like

a lost child forgetting its way home?”

– Zhuangzi

In the famous Jewish settlement of Chelm, where All Things are Exemplified, the village Communist and the village rich man, Mr. Derech Eretz, were having an argument in the street one day. The Rabbi happened along, and they both turned to him to settle things.

“It’s all blah-fibble grumtious, and figgety noggle fram,” explained the rich man, although to keep it short I’m only reporting the important points.

“Yes,” said the Rabbi. He stroked his beard, and thought for a second. “Yes, you’re certainly right.”

The Communist was of course incensed. “Frang-spozzle Marx gwanzwang, and postulation of The Mondollian Pasterfockh,” to summarize his argument.

“Yes,” said the Rabbi. He stroked his beard, and thought for a second. “Yes, you’re certainly right.”

The village storekeeper had been watching all this, and he was puzzled. “But Rabbi,” he protested, “first Eretz said his piece, and you said he was right. Then our Red friend said the exact opposite, and you said he was right. That can’t be right, can it?”

“Yes,” said the Rabbi. He stroked his beard, and thought for a second. “Yes, you’re certainly right.”

, *****************************************

Now that isn’t the punch line.

The punch line is, some days I think about that story and it makes perfect sense. Other times it makes no sense to me whatsoever. Does this possibly have anything to do with the fact that conflict resolution theory is difficult?

-dlj.

Yes, you’re certainly right.