According to the Beijing Chinese Character Study Bureau, there are exactly 91,251 Chinese characters in use today, from which one could derive an almost infinite number of words and expressions. We’ve narrowed that vast pool of linguistic possibilities to just five entertaining Chinese phrases. We hope you enjoy them as much as we do.

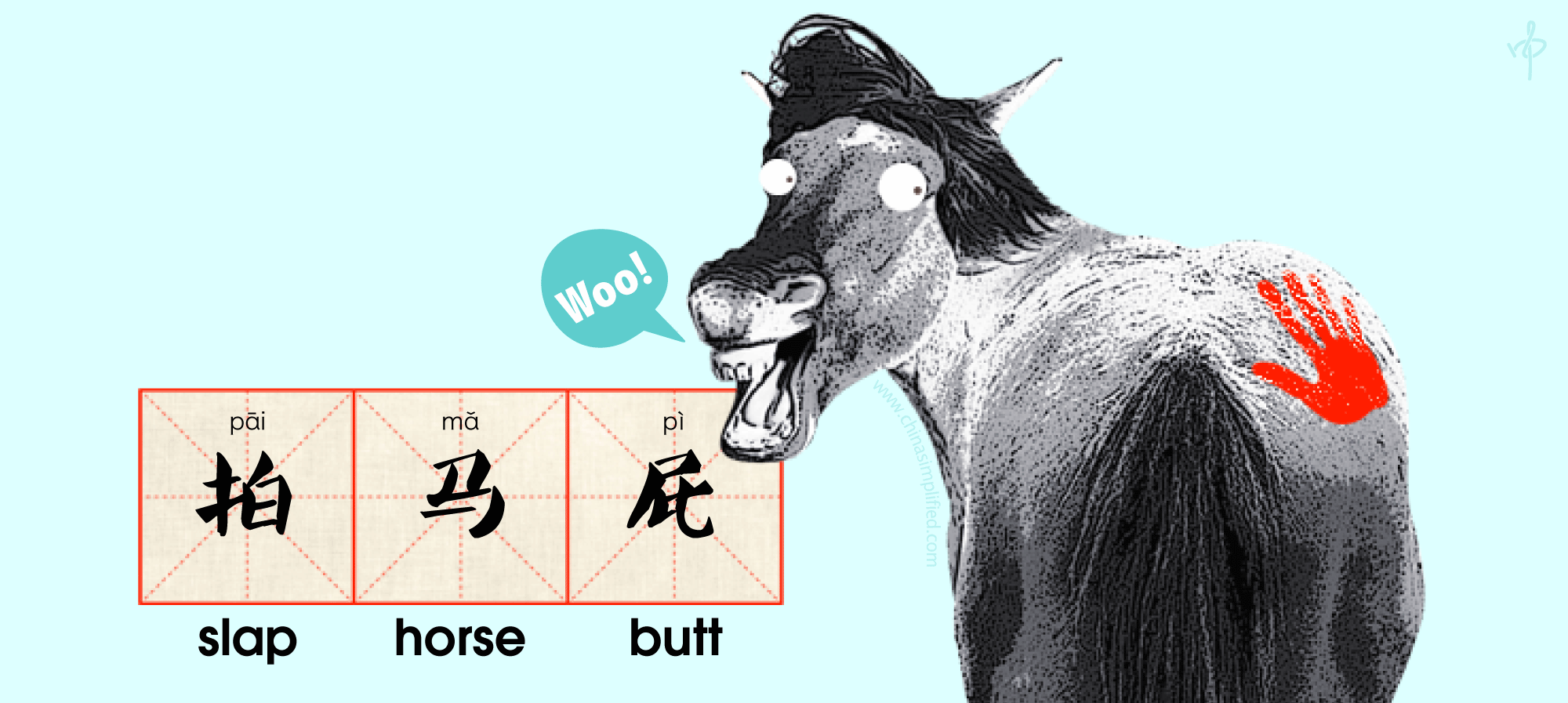

1. 拍马屁 pāi mǎpì

Meaning

To flatter somebody (lit. pat horse butt)

Background

The best way to make someone happy is to compliment his horse. At least that was true during the Yuan Dynasty (1271- 1386) when Mongolian greetings went beyond mere hellos. A little pat on the horse’s ass along with a “good boy” was also paying a compliment to its master. Over time, people developed the habit of praising the horse regardless of its true condition, hence the meaning of this phrase.

Example

Xīn lǎi de zhùlǐ chǔle pāi mǎpì, shěnme dōu bù hùi.

新来的助理除了拍马屁,什么都不会。

Apart from sucking up to people, the new assistant can’t do anything.

2. 东西 dōngxi

Meaning

Things (lit. east west)

Background

A great general word that works almost anywhere. It originates from the emperor sitting facing south, with his back to the north. Objects were placed on both sides of the royal hall, so when the emperor pointed to the east or west it was asking for some thing or another.

Example

Nǐ shǒu shàng ná de shì shénme dōngxi?

你手上拿的是什么东西?

What are you holding in your hands?

3. 乱七八糟 luànqībāzāo

Meaning

All messed up, in great disorder (lit. chaos seven eight rotten)

Background

Chinese history is replete with periods of war and chaos, which eventually usher in periods of stability and

prosperity. One such tumultuous time was the seven countries rebellion in 145BCE of the Western Han Dynasty, when Emperor Liu Bang’s power sharing arrangement with his relatives fell apart. Centuries later in the Jin Dynasty, again to avoid the royal family losing control, a similar decision was made to appoint the royal children as kings. The ensuing mutiny had eight kings vying for power. People began referring to these progressively worse periods of suffering using this chaos idiom.

Example

Tā de fángjiān luànqībāzāo, wǒ zhēnde shòubùliǎo.

他的房间乱七八糟,我真的受不了。

His room is a complete mess, I really can’t stand it.

4. 放鸽子 fànggēzi

Meaning

To stand someone up (lit. release the pigeon)

Background

Once long ago, two people agreed to write each other. When the time arrived, both released their carrier pigeons, however, only one pigeon carried a letter. The empty-handed recipient was left wondering, “Why did he only send the pigeon, not the letter?”

Example

Tā yǐjīng fàng le wǒ liǎng cì gēzi le, wǒ zài yě bú huì xiāngxìn tā le.

他已经放了我两次鸽子了,我再也不会相信他了。

He stood me up twice already, I won’t believe him anymore.

5. 马上到了 mǎshàng dào le

Meaning

I’ll be there immediately (lit. on the horse arriving)

Background

The phrase invokes powerful imagery of gallant warriors and bareback stallions on a windswept plain. It sounds fast, it should be fast, but in reality it probably means your meeting is going to start half an hour late.

For more on this phrase and other delightful Chinese ambiguities, download the free chapter “Embracing the Ambiguity” from our new book China Simplified: Language Empowerment. See “Get Your Free Chapter” box on the top right of this page.